- Home

- Walter Abish

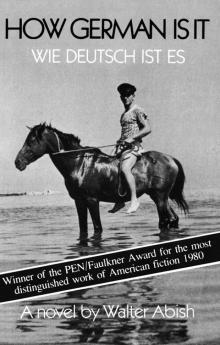

How German Is It

How German Is It Read online

PART ONE

The edge of forgetfulness

.

1

What are the first words a visitor from France can expect to hear upon his arrival at a German airport?

Bonjour?

Or, Guten Tag?

Or, Ihren Pass bitte?

And how does the name Ulrich Hargenau ring in the German ear? Does the name Hargenau remind the official who is examining the passport of a recent—well, not so recent—trial in which the Hargenaus, at least some of the Hargenaus, were linked to what the press recorded as a pathological and maniacal attempt to overthrow the democratic government of the Bundesrepublik.

However, Ulrich has nothing further to fear. He is not asked: What is the reason for your visit to Germany, and how long do you plan to stay? Clearly, in his case, the question is not applicable. The usual response to that question, no matter what the visitor’s purpose, is: Oh, for pleasure. True or not, pleasure is acceptable and instantly understood. It is the right answer. The correct answer. There is no earthly reason why anyone should not come to Germany purely for the sake of pleasure. To admire Germany’s remaining castles, churches, cathedrals. Undeniably, whatever it is that brings people to Germany, it does not preclude the inspection of the magnificent Baroque and Gothic architecture, a trip to a few romantic-looking castles along the Rhine, a day or two attending one of a number of Wagner or Beethoven music festivals, and once there, with the Bavarian mountains providing a scenic backdrop, several hours reclining on the sweet-smelling grass while listening to the heavenly music. Then there are the Dürers, Cranachs, and the works of Holbein the Younger, Conrad Witz, Martin Schongauer, Lochner, Baldung, Bruyn, Amberger, and the magnificent Isenheim Altarpiece by Mathias Grünewald at the museum in Colmar. But this by no means exhausts the reason why people visit Germany. They come to peer into their past, to look up their relatives or the places where their parents were born. They come to rediscover their German roots. They also come to visit the grave of Goethe and to walk in a German forest and absorb that spiritual attachment to nature that underlies all things German. They come in droves to study music or drama or to attend the lectures of Brumhold who, now in his late seventies, is still teaching in Würtenburg. It should also be added that occasionally a foreign writer will come to Germany to promote his book, which has appeared in German. By and large the Germans are avid readers. They respect books, they respect the printed word. Of course, writers also come to Germany in search of material. They can use any of the excellent archives in Bonn, Munich, Nuremberg, or Berlin. They are meticulously kept archives going back to the time of Dürer. There is something in the archives on everyone. Hargenau? Most certainly.

Of course, as a German, Ulrich’s return after half a year abroad is taken for granted. No reason why it should not. It passes, as far as he can tell, unnoticed. There is no longer any reason why his name should be on any blacklist. The Hargenaus are decent, upstanding Germans. The best. He is free to come and go. France? Why not? A fondness for all things French is not unusual. It does not invite criticism. The past has been forgotten.

As for the French visitors? There were a few on the plane on which Ulrich arrived in Würtenburg. What is the first thing they would be likely to notice?

Undoubtedly the cleanliness. The painstaking cleanliness. As well as the all-pervasive sense of order. A reassuring dependability. A punctuality. An almost obsessive punctuality. Then, of course, there is the new, striking architecture. Innovative? Hardly. Imaginative? Not really. But free of that former somber and authoritative massivity. A return to the experimentation of the Bauhaus? Regrettably no. Still, something must be said in favor of the wide expanse of glass on the buildings, the fifteen-, twenty-story buildings, the glass reflecting not only the sky but also acting as a mirror for the older historical sites, those clusters of carefully reconstructed buildings that are an attempt to replicate entire neighborhoods obliterated in the last war.

And how can a visitor from France or Switzerland or America fail to be impressed by the well-mannered, well-behaved, and orderly people in the streets, in the bustling stores, in the pleasantly crowded restaurants and at the well-attended performances in the theaters and at the opera. As a rule Germans are only too happy to be of assistance to a stranger, a foreigner. True, now and then—it could happen anywhere else—this smooth and agreeable surface is broken by a sudden boisterousness, an unexpected violence, an outburst punctuated by the pounding of beer mugs on a table until they shatter, not to mention the broad, red-faced, meaty anger that is thrust aggressively forward and made to appear, with its accompanying black leather coat and black leather gloves, even more threatening, more menacing than it actually might be. But aside from this occasional disruption, the visitor to Germany, and to Würtenburg, cannot help but be overwhelmed by the well-designed highways, die Autobahn, by the fast-moving, well-constructed automobiles, gleaming Mercedes, Audis, BMWs, Porsches, VWs, by the cheerful good-natured, trusting faces, by the prosperous well-stocked stores and supermarkets, by the magnificent landscapes, die Landschaft, the serene pine forests, the lakes, the Bavarian mountains, and the blue sky, der blaue Himmel, and by the new Germany that is emerging: industrial plants, well-designed dams and bridges, modern farms, new urban centers—of which Brumholdstein, named after the philosopher Brumhold, is only one example—and by the large number of tall blond men and women, many wearing leather coats or jackets. But why this curious predilection for leather?

And where does the visitor to Würtenburg stay?

In a one-, two-, three-, or four-star hotel, in a Gasthaus, in a rented apartment or a furnished room let by the week or the season. But preferably in one of the better hotels, hotels that still pride themselves on their punctilious service, their cuisine, and their well-trained multilingual staff.

Ulrich Hargenau signs the hotel register with a practiced flourish.

No unnecessary questions. He is promptly recognized and accepted as a German. Even the name is familiar. And the face? Yes, the Hargenaus are well known in Würtenburg. It is no secret that in some circles his father, Ulrich von Hargenau, is considered a hero. Hargenau? Of course. The fellow who was executed in ’44. No need to say more.

Room 702. A view of the river. Also, it so happens, a view of his former neighborhood, where he spent five years with Paula. Was it five? 702 is a large pleasant-looking room with twin beds. Immense tall mirror over the mantelpiece. Heavy oak shutters on the windows. Two upholstered chairs facing each other across a square black table. Fresh flowers in the tall blue vase. Nice touch. A telephone within reach of the bed. A faint smell of turpentine.

His brother has three separate listings in the Würtenburg phone book. One for the office, two for the residence.

His brother does not conceal his annoyance on the telephone. You’re back in Germany and you didn’t let me know that you were coming? You’re staying in a hotel? You’ll call me in a few days? Is anything the matter?

These days it is possible to arrive in Germany without the slightest fear of an imminent clash with someone in authority. No, there is no reason whatever to fear the Germans any longer. Any fear, if it still exists, if it still lies dormant in the visitor, is simply preposterously unrealistic. It is a fear left over from another period and, most likely, represents nothing but a deeply buried desire to retain the image of the Germans as collectively dangerous and destructive, bent on destroying and eradicating anything that might remotely be considered a threat to their existence. No. How can anyone possibly fear the Germans, now that they have come to resemble all other stable, postindustrial, technologically advanced nations, now that their buildings are no longer intrinsically German but merely like everything else constructed in Germany, well built, solid, intended

to last—and that their language, die deutsche Sprache, as once before is again absorbing words from other languages. Still, notwithstanding the doubtful foreign elements in the language today, the German language remains the means and the key to Brumhold’s metaphysical quest; it is a language that has enabled him, the foremost German philosopher, to formulate the questions and the solutions that have continued to elude the French- and English-speaking metaphysicians. How German is it? Brumhold might well ask of his metaphysical quest, which is rooted in the rich dark soil of der Schwarzwald, rooted in the somber, deliberately solitary existence that derives its passion, its energy, its striving for exactitude from the undulating hills, the pine forests, and the erect motionless figure of the gamekeeper in the green uniform. For that matter, Brumhold might well ask of the language, How German is it still? Has it not once again, by brushing against so many foreign substances, so many foreign languages and experiences, acquired foreign impurities, such as okay and jetlag and topless and supermarket and weekend and sexshop, and consequently absorbed the signifiers of an overwhelmingly decadent concern with materialism? Or is that no longer of interest to the scholars and teachers and writers, but only a matter of concern to the businessmen who are daily trying to sell dishwashers to people in Ethiopia?

At any rate, it is possible for a foreigner, a Frenchman, for instance, to arrive in Würtenburg without recognizing any distinctly German features, for the houses by now resemble the houses in many other European cities, and upon landing, the stranger discovers that the new airport resembles the new airports to be found all over the world, in Rio, in L.A., in Denver, and in Dayton. This in itself is liberating. For is it farfetched to believe that as things begin to look alike, this universality of design will profoundly affect the inhabitants, and more and more Germans and Frenchmen and Americans will begin to think and act alike? As a result of which one day, in the near future, it will be possible to listen to Bach or Beethoven on German soil without feeling the immediate need or obligation to register—that all too familiar, all too ready German awe and reverence with which these composers were listened to in the past: an awe and a reverence that made it obligatory on the part of the listener to communicate his or her ecstacy after listening to a recording, for instance, of Fürtwangler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic on an old 78 Deutsche Grammophon recording, recorded in those heady days of 1941 or 1942. At that time the appropriate response being: hervorragend, fabelhaft, gam ganz schauderhaft, immens, toll, unglaublich.

But why on earth should anyone wish to visit Würtenburg?

Surely not just to visit the historical museum housing a small collection of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century drawings, including two diffidently painted landscapes allegedly by Dürer, or to see the Alperger Castle, which houses a recently restored segment of a large Tintoretto, depicting a seated, docile-looking greyhound and a footstool as well as part of an ornate wine goblet, and the Cranach charcoal study for his painting The Judgment of Paris, or to tour the Ludowitz Abbey or the recently reconstructed Meronthal Cathedral library or the Baron Mintz miniature porcelain collection or the Gussl waterfall. Though Würtenburg is not a tourist attraction there is a great deal to see for the inquiring visitor with a passion for art and history. However, what is on view is dispersed, poorly displayed, and in general inferior to what is available in Munich, or Nuremberg, Frankfurt, or Cologne. True, Würtenburg possesses a small but outstanding botanical garden and a zoo, a gift of the former king of Naples, Joseph Bonaparte, presently consisting of two zebras, one elephant, one hyena, one leopard, four polar bears, and seventeen mountain goats. The city had dutifully replaced all the animals that had been killed and in some cases eaten during the war. Then there is the stamp and numismatic collection of Baron von Hirtenberg, whose great-grandfather, a Jewish furrier, converted to Catholicism. Now housed in the Hotel Auf der kleinen Stufe, its more valuable stamps and coins are kept under lock and key on the ninth floor, but visitors may inspect the exhibit on the mezzanine between the hours of two and four. The taking of photographs is strictly prohibited. The Hirtenberg Marken Sammlune catalog is on sale at the public library and in the hotel lobby. Proceeds of the sales go to the upkeep of the World War I monument on the Hofmühl Gasse.

In spring and summer foreign visitors are not uncommon in Würtenburg. However, after a few aimless days sightseeing they leave, heading for the mountains or the museums and other pleasures that Munich can provide. There is nothing to keep them in Würtenburg, unless the reason for their visit is to look up a friend or relative or attend Brumhold’s lectures, or—unlikely as it may be—seek out the buildings designed and constructed by Helmuth Hargenau. A few—for reasons that are not spelled out—attempt to interview the architect’s brother, Ulrich Hargenau, the author of Now or Never, Once Too Many, What Else?, and Exactly, or, failing that, hope to locate some former friend or acquaintance of one of the imprisoned members of the Einzieh group, the left-wing radicals who had organized their first acts of public disobedience in Würtenberg, possibly in the hope of acquiring some information on the Hargenau family. Still, some visitors remain content simply to stroll about with no specific purpose in mind other than to spend a few days in an old German city, if possible in the company of one of those tall attractive blondes, one of those sleek-looking women in high heels with gold bracelets and gold earrings—a white face and a shrill, ear-piercing laugh. Others are happy to spend as much time as possible in the cafes that line the embankment, drinking coffee, eyeing the people that pass, and gorging themselves on the pastries, rich German pastries, unforgettable pastries and cakes for the visitor with a sweet tooth.

Nothing can be ruled out.

In the past the French came to Germany less with the desire to understand it than with a zealous desire to interpret, to analyze it dispassionately, something for which their training at the École Normale Supérieure or the École des Hautes Études and the French language superbly equipped them to do. Incidentally, Würtenburg was one of the cities visited by Madame de Staël, who so unsettled Goethe and Schiller with her questions during her stay in Germany. All this is documented. The question remains, do the Germans still expect to be asked embarrassing questions about their past and about their present and what, if any, ideas they may have about their future?

Ulrich contemplated the city from his seventh-floor window. To his left, the old Jaeger Bridge, a graceful-looking bridge spanning the Neckar. Or to be quite precise, a bridge that resembled the old Jaeger in every detail, the old Jaeger having been destroyed in the war. Replicas of this kind testify to a German reverence for the past and for the truth, a reverence for the forms and structures upon which so many of their ideals have been emblazoned.

Next. Strolling along the Hertlanger Haupstrasse, a street that in the late afternoon was crowded with shoppers and people leaving their offices, Ulrich came to a stop in front of a tobacconist, pleased to see in the window a pack of the French cigarettes he had become accustomed to smoking. No one gave him a second look when he bought a pack. These trifles play a greater role in one’s life than one is prepared to admit. He bought a small spiral notebook at Heller’s Stationary, where a clerk appeared to recognize him. Not by name, but merely as someone who at one time used to buy supplies there. Continuing in the direction of the university, he ducked into a department store and bought a blue shirt with thin red vertical stripes. Turning left on Johannes Platz carrying his purchase, he entered a bierstube, ordered a stein of beer, and then, seeing someone at the next table with great gusto eating knackwurst and potato salad, ordered a plate as well. The knackwurst was ordered on an impulse. Later, as he passed a bakery, he had to restrain himself from entering.

Next. Essentially a pleasant aimless stroll, looking—as if for the first time—at Würtenburg’s buildings, at the war memorial, the churches, the objects in the shopwindows: lamp shades, silverware, carpets, radios, furniture, food, all attractively displayed—although not with the French flair to which he had, after only

a six-month absence from Germany, grown so attached. It was something that his fellow countrymen, despite all their theories on aesthetics, their determined search for perfection, seemed to lack. In any event, it was difficult to believe that life could ever have been different here. And that these buildings were all recently constructed.

Next.

What is well known?

What is not known?

What is surmised?

What is omitted?

What is distorted?

What is clarified?

What is sensed?

What is dreaded?

What is admired?

What is concluded?

What is rejected?

What is visible?

What is disapproved?

What is permitted?

What is seen?

And what is said?

When Ulrich telephoned his brother, he asked himself: What can I possibly tell him that he doesn’t already know?

From where are you calling? his brother kept repeating.

And Ulrich finally said: I am returning from the edge of forgetfulness.

PART TWO

The idea of Switzerland

.

1

A glorious German summer.

Oh, absolutely.

Easily the most glorious summer of the past thirty-three years.

Thirty-three years? Certainly, he agreed.

When his father, Ulrich von Hargenau, was executed by a firing squad early one August morning in 1944 his father’s last words were: Long live Germany. At least that’s what Ulrich had been told by his family. His father had been killed in a tiny cobblestone courtyard. What was the summer of 1944 like? Active. Certainly, active.

One runs little or no danger in speaking of the weather, or writing about the weather, or in repeating what others may have said on that subject. It is safe to conclude that people discussing the weather may be doing so in order to avoid a more controversial subject, one that might irritate, annoy, or even anger someone, anyone, within earshot. He was past avoiding risks. Just a few weeks after his return from Paris he narrowly avoided being killed on a deserted side street by a driver of a yellow Porsche. It was a beautiful summer day, and he was thinking of getting started on his new book, the one that was based on his stay in Paris. Ulrich was convinced that the driver of the Porsche had intended to kill him or maim him for life. Yes, definitely. He was going to be put out of action. There is little risk in writing this. He had not recognized the driver, whose face he saw for a split second. It was not an unattractive face. It was a German face, like his own. A determined and somewhat obdurate face, a face that Dürer might have taken a fancy to and painted or sketched. Consider yourself lucky, said a passer-by, after having helped him to his feet. The passer-by took it for granted that Ulrich spoke German. He also, Ulrich assumed, took it for granted that what he had just witnessed was an accident, just as Ulrich took it for granted that it was not.

How German Is It

How German Is It