- Home

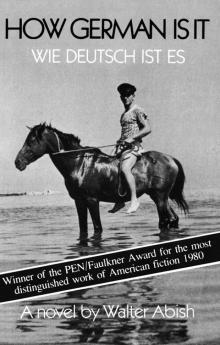

- Walter Abish

How German Is It Page 2

How German Is It Read online

Page 2

You really ought to take greater precautions, said his brother Helmuth when Ulrich mentioned the incident. And why on earth did you decide to return to Würtenburg in the first place?

Because I was tired of hearing everyone around me speak only in French, Ulrich replied flippantly.

Well, try not to take too many risks.

The Hargenaus were not known for their humor. But then his brother might say: After all, what’s so funny about having your head smashed in?

.

2

What was his brother saying?

You should never have married Paula.

I was crazy about her.

If our father hadn’t turned out to be a bloody hero and your name wasn’t Hargenau, you’d be doing ten to fifteen behind bars. Maybe they’d permit you to have a typewriter, Helmuth added as an afterthought.

His brother had not yet had an opportunity to design a house of detention, as it is now called euphemistically, but he had designed a large assembly plant for Druck Electronics, an airport in Krefeld, a library and civic center in Heilbronn, another factory for Stupfen Plumbing, and at least half a dozen apartment buildings and several office buildings, in addition to the new police station and the new post office in Würtenburg. Helmuth had also designed the house in the country where he and his family spent most of their weekends and their vacation each summer. Ulrich had to admit that Helmuth worked harder than he did. He worked incessantly, spending a good part of the day on the phone, directing, cajoling, changing plans. He never seemed to lose his temper. He was never impatient. Helmuth took after their father. And Ulrich?

As Ulrich was leaving after spending a weekend with his brother and his family, Helmuth said: We must get together, you and I. We really must sit down and discuss things. Ulrich did not have the heart to tell him that really there was not anything left to discuss. At one time, years ago, they had their differences; now these hardly mattered. He did not even remember what they were about. Perhaps he had been envious of his brother’s success, a success that Helmuth took for granted. He expected it. He even confided to Ulrich that if their father had not been such a complacent and self-assured aristocrat, he might have made a better conspirator. At least he was shot, instead of being left to dangle from a meathook in front of a film crew recording the event.

Helmuth rose each morning at six-thirty. By seven-ten the entire family was at the table having breakfast. No one was ever late for breakfast. The children watched Helmuth intently. They waited for him to signal what kind of a day they could expect. Helmuth looked at his watch and pursed his lips. He had two important meetings first thing in the morning. He confided everything to Maria. She was blonde and blue-eyed like him. She faced him squarely across the table. She dutifully informed him how she intended to spend the day. Nothing was too trivial to be omitted. The children listened intently. They were seeing at first hand the life of an adult world unfold. It was a real world. They were aware that each day their father contributed something tangible to that world. Each day a number of buildings all over Germany rose by another few meters and came closer to the completion that initially had its roots, so to speak, in his brain. By now, the entire family knew their architectural history, backwards and forwards. They knew how an architect, in order to proceed with his plans, must cajole, reason with, and reassure his nervous and uneasy clients. The children gazed into Helmuth’s blue eyes and were reassured. The English suit spoke for itself. At a quarter to eight he was at the wheel of his car. The children admired him. His wife admired him. His secretary admired him. His colleagues admired him, but grudgingly. His draftsmen admired him. His clients more than admire him, they attempt to emulate his relaxed approach to anything that may come up. What they all saw was a tall, blond, blue-eyed man wearing a well-tailored English suit, preferably plaid, and a solid-color knit tie several shades darker than the button-down shirt. He shook hands with a firm dry grip. He never perspired. Not even on TV, with the bright floodlights focused on him. Perfectly at ease, he addressed the TV audience, the vast German audience, discussing his favorite subject, architecture. The splendid history of architecture. Greece, Rome, Byzantium, a slow parade of architectural achievement culminating in the new police station in Würtenburg. Most of Würtenburg tuned in to listen to Ulrich’s brother, amazed at the riches he presented for their edification: the riches in their immediate vicinity, the riches of past genius. Helmuth Hargenau, he’s something else, they would say, shaking their heads in disbelief.

And his brother Ulrich?

Best not talk about him. One never knows who may be listening.

.

3

On his desk, a small framed photograph of his father, taken in his father’s study. In the background to the left of his father, a drawing by Dürer. In the lapel of his father’s jacket, the gleam of a tiny swastika. The photograph had been taken in the summer of 1941, a good summer for Germany. Next to the photograph of his father was one of Paula, his former wife. A snapshot, taken on an outing. Had she, by then, already informed him that a few of their friends had stashed a couple of cases containing World War II hand grenades in their cellar? In our cellar? In our cellar? She had mentioned it quite casually, as if they were cases of champagne being stored for a surprise party. He could not help admire her incredible coolness. Her apparent indifference to the danger of what she was doing. Like his father, who removed the swastika from the lapel of his jacket in 1942, she believed in causes and justice.

Now that he knew where she was, why didn’t he make an effort to get in touch with her?

Answer.

Answer immediately.

.

4

A glorious summer. A glorious German summer.

Repeat.

Sometimes he felt as if his brain had become addicted to repetitions, needing to hear everything repeated once, then twice in order to be certain that the statement was not false or misleading. He found himself repeating what he intended to do next, even though he would be the first to acknowledge that repetition precluded the attainment of perfection or, as the American thinker Whitehead put it: Perfection does not invite repetition.

His brain kept urging him to repeat. It insisted on a rerun of everything he undertook to do. It kept asking: Why am I here? Now? And what do I plan to do? Tomorrow? The day after? And the day after?

The summer this year is really quite exceptional. It is almost (take note of the almost) perfect. Not too hot during the daytime and pleasantly cool at night. He could be imagining this, but the satisfied looks on the faces of the people he saw daily reflected—of this he was convinced—their contentedness with the weather and, in turn, with their pleasant and harmonious surroundings and, in turn, with their more or less amiable friends and relatives and, in turn, with the intimate affairs that are now and then bound to occur, particularly when the individual in question is not overly hampered by discontent or some emotional disturbance, something that might impair his or her ability to judge people and, among other things, to respond correctly to a sexual overture the instant it is made.

He had met Paula in the Englischer Garten in Munich. He had been bleeding from a cut he had received when a policeman punched him in the face at the public rally in which he and a group of his friends had participated. One of the first questions she had put to him was: Have you ever felt the temptation to blow up a police station? He had just laughed.

You’ve really taken leave of your senses, Helmuth had said in his most pompous and condescending manner when Ulrich had mentioned that he intended to marry Paula. Father would have admired her guts, Ulrich had said. He had guts, all right, but little else, replied Helmuth, otherwise he would have headed for Switzerland. Helmuth had met Paula for only a few hours. What was it that Helmuth could see in her that he had failed to see?

Answer.

Answer immediately.

The characters in his book can be said to be free of emotional disturbances, free of emotional impairments. They

meet here and there, in parks or at public rallies, and without too much time spent analyzing their own needs, allow their brains a brief respite, as they embrace each other in bed. You’re a pretty good lover, Paula admitted, but are you able to blow up a police station?

What actually constitutes an emotional impairment?

Could it be that an inner turmoil, an absence of serenity, an unresolved entanglement, self-doubt, self-hatred may be due to nothing more serious than a person’s inability to appreciate the idyllic weather?

In this instance, the weather was perfect in Würtenburg and its immediate surroundings. Now, at this moment, along with the entire population of Würtenburg (approximately 125,968 according to the latest census) he too was experiencing the fine weather. He felt completely relaxed. Nothing on his mind. Nothing but how he was going to spend the pleasant day. He did not ever expect to hear from Marie-Jean Filebra, or from his former wife, Paula Hargenau—the first, he assumed, still in Paris, the other now free to go wherever she chose.

Repeat.

Wherever she chose.

The brain keeps persisting that it can survive on images alone. No words.

Helmuth, on meeting him in the hotel after his return from Paris, promptly informed him that Paula was now living in Geneva. Helmuth seemed put out when he laughed. Uncontrollable laughter. Geneva? What on earth could she be doing in Geneva? Helmuth smiled awkwardly, then shrugged his shoulders. I guess she must be fond of the place.

Paula. In Geneva? Impossible.

Apparently he was mistaken. He still did not know what she was up to in Geneva but had no intention of inquiring. He did not want to embarrass her with his questions, his interest, or his presence. But he was happy that she was free.

I still love Paula Hargenau and I do not love Marie-Jean Filebra, he wrote in a notebook in Paris. That was the first entry he had made in his Paris notebook. Was he aware that he was taking notes for a future book? Was he aware that he would eventually return to Würtenburg and there, in a new apartment, quietly piece together his next novel, a novel based on his six months’ stay in Paris, a novel based on his affair with Marie-Jean Filebra, a novel based on his desire to efface everything that had preceded his trip to Paris.

He was not hiding in Würtenburg. He was listed in the phone book. If his former friends wished to locate him they could easily do so. Each morning he stepped out to get the paper. In the afternoon, around four, he took a walk. Each morning, each afternoon, more or less at the same time. In that respect he presented no problem for anyone who might wish to kill him. The man in the Porsche could give it another try.

Frequently, two or three times a week, he received a letter from some anonymous person who appeared to hate him with a greater passion and intensity than he had ever been able to hate anyone. Were all these letters written by lunatics? He could have given them to the police; instead he tossed them into a drawer of his desk.

Maria, his sister-in-law, called him every three or four days. Presumably at the suggestion of Helmuth. He could hear his brother saying: Best to keep in touch with him. You never know. But what shall I say? Oh, talk to him about books … Whenever she called she tried to elicit from him what he was writing. Is it autobiographical?

Existence does not take place within the skin, he replied, quoting Brumhold.

Nonsense.

Only Maria is able to put him on the defensive by saying: Nonsense.

It’s true.

Repeat.

I am telling you the absolute truth.

.

5

An earnest-faced young woman moved into the empty apartment above his. Since the Hausmeister was off duty, he helped her carry a few heavy cartons of books from the sidewalk to the elevator. What floor are you on, he asked. Five, she said. Ah, you’re moving into the apartment above mine. She smiled. Well, I’m not very noisy.

Würtenburg is gradually emerging from its medieval past, to which its inhabitants are still so attached … the medieval past that is etched on so many of the faces of the people who live here. Helmuth and he are no exception. He gravely stares at his face in the mirror and sees Germany’s past sweep by before his eyes.

It seemed likely that a young, earnest-faced American woman when visiting Würtenburg could not help but see the world of Albrecht Dürer come to life. Dürer could easily become the visitor’s point of reference or perhaps even guide, as he or she leisurely walked along the main street past the cathedral designed by Müse-Haft Toll, with its frescoes by Alfredo Igloria Grobart and stained-glass windows by Nacklewitz Jahn, and then past the World War I monument on the left, a bronze riderless horse rearing up on its hind legs, the four dull metal tablets on its granite base bearing in alphabetical sequence the names of those killed in action. There were at least six Hargenaus, naturally all officers, who died in World War I, and another half a dozen (Ulrich von Hargenau’s name not included) whose names were carved into the large slab of marble now placed, after a heated debate, behind the Schottendorferkirche, a somewhat out of the way part of the city, considered at the time by many as a more suitable spot for a World War II monument. After turning right at the public library it was only five minutes’ brisk walk to the university, where old Brumhold was still teaching philosophy after an enforced period of idleness, the result of too many reckless speeches in the ’30s and early ’40s, speeches that dealt with the citizen’s responsibilities to the New Order. Poor Brumhold. Once he had stopped dealing with abstract theories and was able to make himself understood to one overcrowded lecture hall of students after another, the ideas he came to express were reinforced by statements such as: We have completely broken with a landless and powerless thinking. But by now Brumhold’s former platitudinous speeches have been forgotten. His students swore by him, and his classes were always crowded. Sometimes as many as four hundred sat in a cavernous, drafty auditorium, attentively listening to Brumhold as he lectured on the meaning of a thing. He knew how to rivet their attention. At heart he was an excellent performer. What is a thing? he asked rhetorically. Brumhold, it must be pointed out, was not referring to a particular thing. He was not, for instance, referring to a modern apartment house, or a metal frame window, or an English lesson, but the thingliness that is intrinsic to all things, regardless of their merit, their usefulness, and the degree of their perfection. The reference to perfection, however antithetical and invidious it might appear to be to the thinking of Brumhold, was made because the mind is so created that it habitually sets up standards of perfection for everything: for marriage and for driving, for love affairs and for garden furniture, for table tennis and for gas ovens, for faces and for something as petty as the weather. And then, having established these standards, it sets up other standards of comparison, which serve, if nothing else, to confirm in the minds of most people that a great many things are less than perfect.

.

6

I still love Paula Hargenau and I do not love Marie-Jean Filebra, he wrote in his Paris notebook, while staying in a tiny squalid hotel on Rue des Canettes in the vicinity of Saint Sulpice. Those were the first lines in his notebook. Was he aware that in all likelihood he was taking notes for his next novel. Was he aware at the time that in a few months he would return to Würtenburg, there at his leisure to decipher pages of hastily scribbled notes depicting a gradual and at the time almost inexplicable withdrawal from Marie-Jean that toward the end of the affair, shortly before his departure from Paris, intensified, so that what had initially prompted a cautious act of withdrawal turned into a feeling of revulsion and physical repugnance for the woman he had shortly before professed to love. Ahh, the mysteries of love.

.

7

His brain relied on the words in his notebooks to designate its expectations. In his case a future predicated on words. But on words that in themselves would not bewilder the Hausmeister who daily greeted him with: Looks like another fine day.

Repeat: Looks like another fine day?

For all he knew the Hausmeister may have been one of the squad that shot his father. Admittedly, it is somewhat unlikely. And if he had, he was under orders. If you are a member of an execution squad, you can’t pick the people you would like to shoot. Or can you?

It was another glorious day, and he really did not want to be anywhere else in the world.

He was convinced that his feelings in general with respect to the glorious summer day were shared by the people now casually walking down the Hauptstrasse, stopping every now and then to gaze briefly into a shopwindow, looking at the things that were on display, sometimes peering into the interior of the store to see if they could spot a familiar face, no doubt a German face, a Dürerlike face of an acquaintance or friend.

How German Is It

How German Is It